the sustainable impact of the illicit drug trade.

The illegal drug trade is one of the most complex global industries. Not bound to any ethical or legal framework, it has thus rapidly expanded in the past century. Today, the production and obtainability of illicit recreational drugs are at an all-time high. (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2018). Profit, regardless of the consequences, is the illicit drug trade's main agenda, while sustainable development has continually been ignored as environmental and social degradation continues. This paper will highlight sustainable principles in the illicit drug trade, explaining the barriers and relationships halting sustainable development.

Defining Sustainability

The contemporary Western term for 'sustainable development' was officially defined in 1987 by the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations stated as; "sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." (as cited in Rack, 2014)

This Western definition of sustainability became popular for English speakers in the mid-20th century. However, other Western languages such as Dutch, German, and French had already used similar terms for centuries, such as nachhaltigkeit, nachhaltig, durabilité, and duurzaamheid or duurzaam. (Jacobus, 2006)

Germany began coining sustainable concepts as early as the 16th century, becoming more common in the 18th century. The first official use of a sustainable term (Nachhaltende Nutzung) was in The German forestry circles by Hans Carl von Carlowitz in Sylvicultura Oeconomica in 1713. Inspired by Hans, Marchand and Wilhelm Gottfried Moser coined the sustainable term 'Ewige Wald' (Eternal forest) to refer to the regeneration of forests and ecosystems (Jacobus, 2006).

The start of sustainable thinking in Western culture originated from an offshoot of the development of classical civilization; As humanity explored their understanding of time and progress, Concepts such as unlimited economic growth aligned with classic society values and became widely formulated into the model society (Jacobus, 2006).

However, this growth in many classical civilizations was causing environmental problems such as deforestation, salinization, and land degradation. In response to these issues, Philosophers and scholars such as Plato, Strabo, columella, and Pliny the Elder were already discussing environmental degradation by humans, such as farming, logging, and mining. (Jacobus, 2006). The Western concept of unlimited economic growth fully matured in the Industrial Revolution. Technological advancement, commercial expansion, and population surged. Industrialization became the catalyst for globalization; unlimited growth became a universal belief, enslaving the globe under a capitalist system. (Jacobus, 2006).

The scale of environmental dangers caused by capitalism had been widely disregarded until WW2. People became more aware of the stakes of rapid population growth, pollution, and resource depletion. From the 1960s to the 1970s, scientific information about these dangers became more present in the public eye. A series of publications from authors about environmental damages generated scepticism about the system and contributed to a wave of anti-establishment and environmental movements. In 1970, the modern terminology for 'sustainable development' was coined by Barbara Ward, founder of the International Institute for Environment and Development (Jacobus, 2006), and soon officialised by The United Nations.

The War on Drugs

In the late 20th century, with newer generations becoming ever more sceptical of the establishment, a sudden trend in drug use was on the rise. This consumption was inspired by popular fashions from the counterculture movement, style subcultures, and the glamorization of drug use (Musto, 1996)

The government's response to this trend was aggressive preventive action, which ironically only increased the rapid economic boom of the illegal drug trade. Most famously, this response in the USA was known as The War on Drugs. Starting in 1971, the War on Drugs was a series of repressive drug laws and aggressive anti-trafficking efforts taken up nationally and internationally to eliminate the supply of drugs (Lopez, 2016).

These repressive efforts not only caused severe environmental and social consequences but also developed the illegal drug trade into a far more sophisticated industry. By challenging and repressing the illicit drug market, traffickers and dealers have created more complex and discrete trafficking, production, and revenue methods. (Mcsweeney, 2015).

The Financial Impact

One of the main ways the illegal drug trade created more discreet revenue was through laundering money legitimizing their cash flow by investing in cattle, coffee, and palm oil. The rural areas laundered for the drug cartels are often taken by unlawful, violent means at the economic expense of local farmers and forest regions logged for agricultural land. (Mcsweeney, 2015). Economic barriers are most apparent on the legal front. Standard government methods to control illicit drug trade often seriously deprive other sectors and heavily fund services that do not create long-term change (UNRISD, 1994).

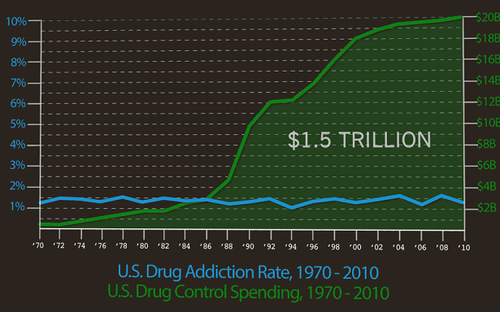

Repressive measures are not economically effective; this diagram explains how, although the US government has invested their money into repressive drug control for several decades, drug consumption has not been affected (Dai, 2012). Instead, this funding has indirectly increased poverty and expanded complex drug distribution (UNRISD, 1994).

The Social Impact

The economic principles of the illegal drug trade present an industry that has developed into a hypercapitalist pyramid scheme, where an imbalance of equity is the driving mechanism. Since the 1970s, repressive government interventions and policies have intensified the overall equity problem in the illicit drug trade. Increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders have been mainly counterproductive, not tackling the root cause of the issue and instead dealing with minor drug offenders rather than charging powerful criminals at the top of the pyramid (Annan et al., 2018). Minor drug offenders often come from poor or ethnic minorities and are the most vulnerable to the pressure of being involved in organized crime, both in rural and urban settings (Annan et al., 2018). For poor or ethnic minority communities, organized crime is intertwined with the culture, often providing income, essential services, and stability that the state fails to provide (Annan et al., 2018). Further pressure on these communities includes the scarcity of job opportunities and social cohesion, leaving drug trafficking or cultivation as the only viable option to obtain a substantial income (Annan et al., 2018). Vulnerable communities often face the brunt of oppressive drug control policies, financially and socially, with police and military action increasing violence, corruption, and prison overcrowding (Annan et al., 2018).

Repressive drug laws also have adverse effects on drug users, increasing violations of human rights occurring globally. These laws are centred on brutal preventive tactics that ignore the root causes of the drug user's consumption. Common themes of brutal prevention tactics include "police harassment, humiliations and physical abuse, forced urine testing, and automatic registration in police records. Locking up people who use drugs in compulsory detention or rehabilitation centres" (Annan et al., 2018, p. 8).

What has been recognized in recent years is that drug laws have only accelerated an imbalance of equity. Government action for the past few decades has solely focused on repressive prevention and enforcement. These methods are counterintuitive to preventing illegal drug distribution in the long term and have left many people marginalized and vulnerable.

The Environmental Impact

Repressive drug policies affect not only communities but also the environment around them. Ecological harm is occurring due to the direct pressure applied by repressive drug policies. This has led to the illicit drug trade pursuing unsustainable practices as a means to avoid the authorities. Direct pressure is carried out through repressive drug control strategies such as forced crop eradication, where the authorities forcibly exterminate land cultivating illicit drugs (Bigwood & Coffin, 2005). Eradication is conducted using harmful pesticides that destroy crops and leak toxic contaminants into the local ecosystem, harming aquatic life, fauna, insects, and soil composition (Annan et al., 2018). A more severe type of crop eradication is aerial fumigation campaigns, which spray harmful pesticides and herbicides over the illicit crop-grown region via aircraft. Studies support that these aerial campaigns use herbicides containing glyphosate, which is known for harmful side effects to humans, including "respiratory problems, skin rashes, diarrhoea, eye problems and miscarriages." (Annan et al., 2018, p.9). Aerial spraying also harms wildlife and crop life, such as chicken and fish farms, leading to toxicity and higher mortality (Annan et al., 2018)

Overall, forced crop eradication has been proven ineffective in combating the production of illicit crops and has led families to subsequent food insecurity, denial of livelihood, and displacement (Harm Reduction International, 2010). What drug eradication strategies have done is lead to a shift in the illicit drug trade. Agriculture and shipment of illegal drugs have moved further into remote environments to avoid detection (Mcsweeney, 2015). Although a tiny global agricultural sector, the illicit drug trade now disproportionately plays a massive part globally in fuelling deforestation and environmental degradation (Mcsweeney, 2015).

From this aftermath, ecosystems crumble, erosion increases, nutrient-rich topsoils decrease, and carbon emissions are poured out from the burning, cutting, and loss of rainforests. (Burns-Edel, 2016). Deforestation is only the beginning of the abuse. Unbound by legal regulations, destructive farming practices are the norm in these remote areas as pollutants are discharged into this ecosystem via the improper and illegal uses of fertilizers, pesticides, and rodenticides. The severity of these effects is increased by soil degradation and biodiversity loss from deforestation, leaving the environment particularly vulnerable to toxification (Burns-Edel, 2016).

Another environmental concern complicating sustainable development is the water footprint of farming recreational drugs, both illegal and legal. For example, A single Marijuana plant has a water usage of 8-10 gallons per day, double the amount needed to farm grapes or tomatoes. This statistic is concerning when considering water scarcity issues, such as drought regions like California, where 70% of the legal cannabis in the USA is grown (Burns-Edel, 2016).

The Energy Impact

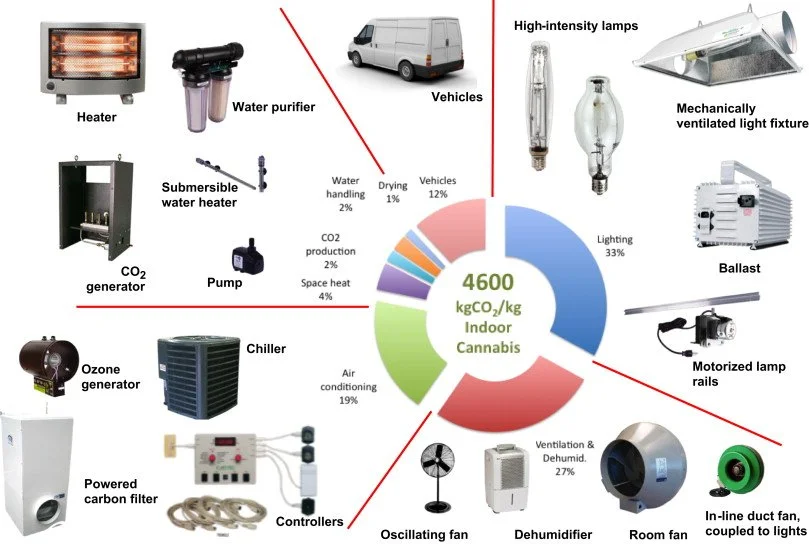

Sustainable measurements like water use are becoming ever more critical when evaluating the sustainability of products. Energy has played an essential factor in these reviews, with unrenewable energy sources linked to a global environmental crisis such as global warming. Energy usage is not widely documented in the illicit drug trade, likely due to the lack of data to estimate energy demands and the lack of legal control over an illicit market (Gamez, J, 2018). However, evaluating the energy usage of farming recreational drugs has become ever more relevant when considering future approaches to drug control, such as legalization (Lopez, 2016). Estimates declared that cannabis production currently accounts for 1% of USA energy usage (Gamez, 2018). The primary source of this energy usage comes from indoor marijuana cultivation, which satisfies half of the legal cannabis demand (Fox, 2018). The main reason for farming marijuana indoors is the controlled environment allowing cultivation all year long and producing higher quality cannabis (Gorman, 2020). Illegally, the benefit of farming indoors is to avoid the authorities, with growers sometimes stealing electricity to obscure their energy use, by tapping into the main electrical line at the risk of electrical faults ("The energy drain," 2011). Energy usage from indoor operations prominently comes from powering appliances such as light bulbs, ventilation fans, and dehumidifiers to mimic the ideal outdoor growing conditions ("The energy drain," 2011).

On average, every kilogram of dried cannabis from indoor farming is the equivalent of 5 tons of carbon dioxide pouring into the atmosphere (Gorman, 2020). These statistics are even more troubling when considering the tiny amount of regulation on the environmental impacts of legalized cannabis. As stated further by Dharna Noor of Gizmodo, "There is little to no regulation on emissions for growing cannabis indoors. Consumers aren't considering the environmental effect either. This industry is developing and expanding very quickly without consideration for the environment." (cited by Fox, 2018).

Discussion

The rise of legalized cannabis discussed in energy principles demonstrates that drug policies are not considering sustainable variables. On the other hand, repressive drug policies are causing far more harm. Prohibition and aggressive tactics have severely increased the poverty line and prevented other legal sectors from applying sustainable drug control solutions for the last few decades (Annan et al., 2018). Aggressive enforcement tactics have inflated the power of illicit drug cartels. By putting the cartels under pressure, the trade has rapidly adapted, creating new trafficking schemes, wider distribution, furthering control over marginalized communities, and corrupting authorities (Mcsweeney, 2015). This situation, when discussing drug control, is commonly referred to as the “balloon effect: what is pushed down in one place simply springs up in another" (UNRISD, 1994, p.10).

This dilemma is demonstrated best in forced crop eradication, where repression methods were used; drug cartels shifted operations into more inaccessible and remote regions. This response resulted in illicit drug cartels damaging the ecological landscape and the authorities leaving communities vulnerable and impoverished, eradicated of their income (UNRISD, 1994). While the government has been diverting their funding, time, and energy into repressive action, the illicit drug trade has taken the place of the government, generating jobs for millions of people in impoverished communities who are discriminated against and marginalized by the state (Felbab-Brown, n.d.).

Conclusion

As sustainable development becomes more relevant, governments have begun to move away from repressive policies. Many drug policy expert now endorses their efforts on rehabilitation, decriminalization, and legalization (Lopez, 2016). The United Nations has focused its efforts on disrupting the illicit drug trade by ending poverty among the most vulnerable within the illegal drug market. (Annan et al., 2018, p. 4). Livelihood projects and enterprise development are suggested to implement this action. Other drug control reforms are looking at disbanding drug control enforcement measures and eradication tactics for marginalized communities to regain trust in the establishment (Burns-Edel, 2016). For the past few decades, Bolivia's experimentation with socially controlled coca production can be seen as an example of the effectiveness of alternative drug control measures. In this case, Bolivia lets coca farmers legally cultivate in fixed areas. The results are a significant reduction in poverty, deforestation, and violence. (Annan et al., 2018).The diagram below further highlights the sustainable benefits of Bolivia’s coca production.