Measuring the Impact of Fashion Micro-businesses in Aotearoa

Foreword

In late November of 2022, I co-wrote an article exploring the behind-the-scenes of the NVV World fashion show for Ratworld Magazine. NVV World was a collective of independent local fashion designers who shared studio space and a similar ethos. Their show presented a particularly unique and authentic experience that approached fashion as a cultural production that could be connective, sustainable, accessible and emotionally meaningful. This moment gave me some hope against my pessimistic outlook on the present state of fashion. Since then, I've been closely observing the fashion microbusinesses in my everyday life and interacted with many different fashion businesses in my gap year, shifting between Ohakune, Wellington and Auckland.

These initial observations converge to construct the topic of this report, Measuring the impact of fashion micro-businesses in Aotearoa.

The relevance of this topic is critical to my goal of producing systematic changes in the fashion industry. Growing up in Aotearoa and travelling overseas a lot as a child, I assessed that New Zealand is culturally and industrially in a niche position on the global landscape. Because of this unique situation, I believe NZ fashion struggles to keep up with today's international fashion. I hypothesise that for Aotearoa to increase national wealth and well-being through our clothing and textile sector, we mustn't copy the Western fashion business model. Instead, we must design an apparel sector best suited to our surrounding landscape. The entrepreneurship and experimental and grassroots endeavours of NZ fashion microbusiness may be the clue to this systematic approach.

Methodology & Limitation

Methodology

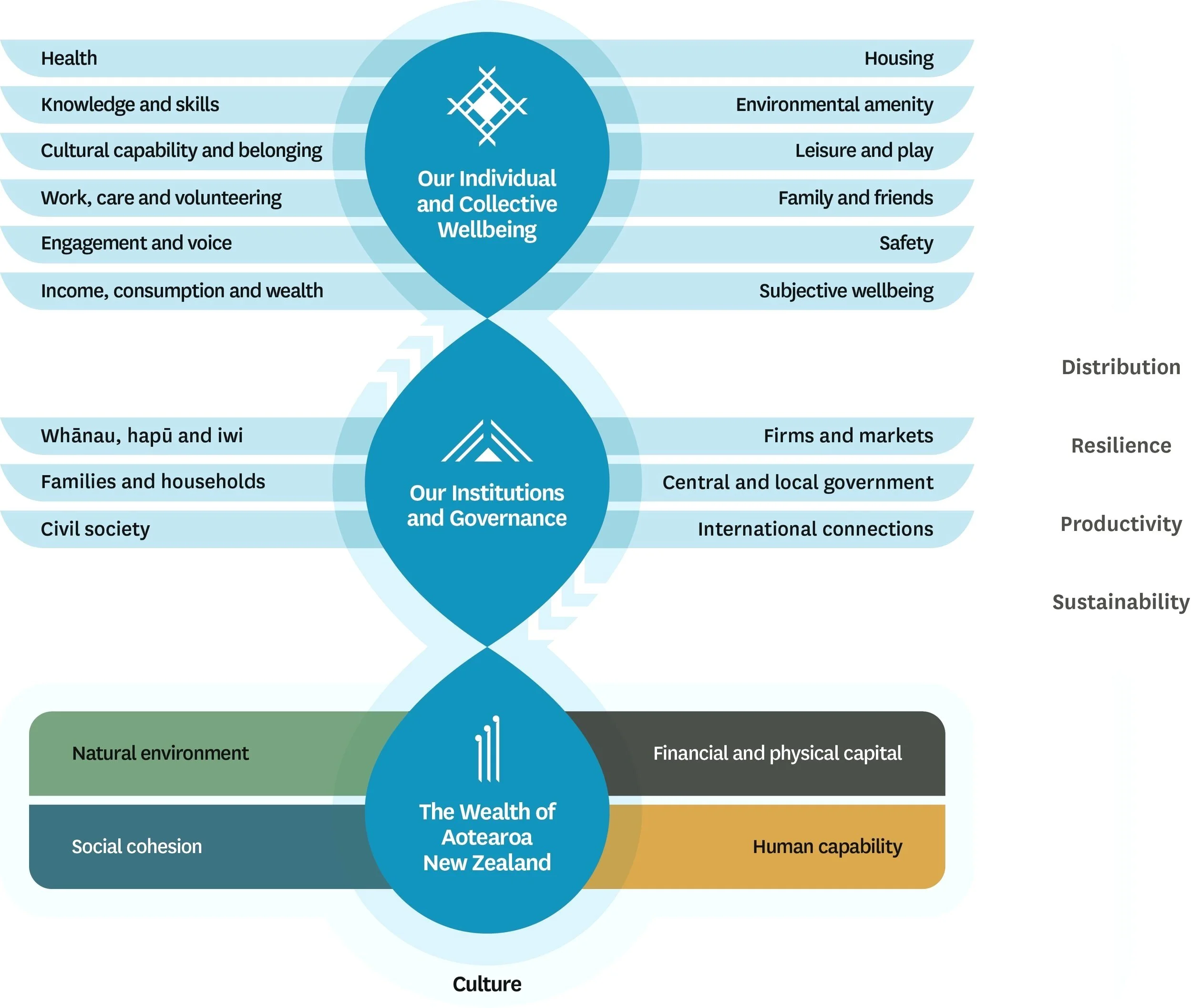

I approach this research report by exploring variables of my topic through contextual investigation and four case studies of local fashion micro businesses to inform my results through analysis of level three of the Living Standard Framework that measures trends of wealth and well-being in present and future Aotearoa (The Treasury, 2021).

Level three of the Living Standard Framework uses four aspects to measure micro and macro domains of well-being and national wealth (The Treasury, 2021). These aspects were cornerstones of how the report's findings were analysed.

These aspects are defined as:

● The natural environment - "supporting life and human activity, whether valued for spiritual, cultural or economic reasons." (The Treasury, 2021)

● Human capability - "People's knowledge, physical and mental health, including cultural capability. " (The Treasury, 2021)

● Social cohesion- "The willingness of diverse individuals and groups to trust and cooperate with each other in the interests of all, supported by shared intercultural norms and values." (The Treasury, 2021).

● Financial and physical capital - "overlapping of three subcategories, Human made assets, knowledge-based property assets and financial assets." (The Treasury, 2021) Finally, culture is an overlapping system in which all these aspects distribute wealth and well-being through shared knowledge (The Treasury, 2021).

Limitations

Several limitations affected this research report. I address these factors to provide transparent documentation of my findings and highlight possible inaccuracies when securing and measuring data.

Time and submission requirement constraints.

This report interviews 3 participants; however, further primary investigative research should be explored before solidifying any impact measurements stated in this report to gain a broader range of microbusiness perspectives, notably outside of Tamaki Makaurau.

These constraints led to only focusing on level three of the Living Standard Framework. To obtain an accurate measurement of impact, further analysis from Levels 1 and 2 of the Living Standard Framework to gain complete insight into measuring market impact, such as how well-being and wealth from fashion microbusiness are being culturally distributed and developed in the local community and nationally.

The complexities of sourcing microbusiness research.

Finding data specifically on microbusiness can be complicated, as microbusiness research is often only considered a subcategory of small business studies. However, my research and investigation have shown that micro businesses should be a separate area of research as their needs and perspectives differ from those of small businesses.

The other dilemma of microbusiness research is that sourcing relevant data can be complicated as each country has a different definition of what is considered a micro-business; this leads to data from overseas countries often being irrelevant because definitions differ from New Zealand laws.

Accessibility and accuracy of financial data.

Due to the disruption COVID-19 has caused in the financial market, it was difficult to assess the actual accuracy of financial data in the present market, with wild differences between pre and post-COVID pandemic financial data (Stats NZ, 2020.).

There was also difficulty accessing data as financial insight services often required payment or subscription to show the full extent of the data and graphs.

There is a lack of definition for the clothing and textile sector in Aotearoa.

I could not source a definition for what is considered the fashion industry in Aotearoa. I could not find any reliable NZ fashion bodies or government entities that provide this information. This lack of definition had a trick-down effect where very few up-to-date Aotearoa-sourced statistics primarily on clothing and textile sectors. Aotearoa-sourced data only mention apparel as a partial subcategory of a larger research body, for example, production or retail. These sector statistics do not fully represent the full scale of employment and business in the fashion industry, mapped by the mindful fashion industry role map.

Figure 2: Mindful Fashion industry role map highlights the diversity of jobs in the local fashion industry. From Mindful Fashion, 2022.

I shall define the fashion industry for this study from two sources: the 'business of making and selling clothing, which follows the increasingly complex consumer desires, demands, and fashion trends in the world' and the (Colovic, 2012, Major & Steele, 2023.)

Contextual Investigation

Forming a contextual framework was incredibly important when approaching this topic. It was the building block of how I should go about my primary investigation and provided an informative reference point for any statements offered in my findings. This research also clarified the configuration of variables in my research topic to better understand the relationship between my findings and the contextual framework. My approach to exploring these variables was sourcing secondary data on the current state of NZ fashion, the history of the NZ clothing industry, and an overview of micro-business operations.

The Current State of Aotearoa’s Fashion Industry

My contextual exploration begins with understanding the financial outlook of the local fashion industry to support any bold statements in our living standard framework analysis.

My main finding was that although Aotearoa apparel market revenue was reasonably small globally at $7.17NZD billion, our CAGR had a remarkably high forecast of +4.39% growth between 2023-2027 (Statista, 2023b.). We can see this notable growth when comparing OECD countries with similar populations. For example, Ireland has a 3.11% CAGR (Statista, 2023a.), and Norway has a CAGR forecast of 2.66% (Statista, 2023c.). This CAGR forecast is particularly striking, considering that most countries are experiencing a decline in growth since the COVID-19 outbreak (Amed et al., 2022). Due to the inaccessibility and turbulence of financial data about the local fashion market, it's difficult to fully understand why our CGAR is exceptionally high (Stats NZ, 2020.). My assumption for the former figure is that NZ consumers have a serious interest in clothing and footwear in NZ, with forecasts predicting a 33.34% increase in consumer spending over the next four years (Degenhard, 2023). However, most of these sales will likely come from overseas-produced apparel, with sales in the local apparel manufacturing sector only standing at NZD 469 million in 2021. (Statista Research Department, 2022)

When looking at the current state of NZ fashion, I look at what is unique about the NZ fashion business and market to gauge better what trends are already happening in the national market. NZ fashion emphasises locality and national identity as a strategy to compete against global fast fashion (Glasson, 2018.). These designs often emphasise sustainability, fair trade and innovation (Catherall, 2021a). New Zealand brands often use various production methods, from local production in-house to high bulk offshore (Glasson, 2018.), focusing on social media and e-commerce to sell to local and overseas buyers (Catherall, 2021a).

When researching the NZ fashion market, there were three main barriers to business growth for New Zealand businesses. These barriers were essential to consider when measuring the impact of fashion micro-businesses and how these variables could impact the analysis.

The first obstacle for Aotearoa's business was globalisation. The world economy is based on international trade; However, this distribution system isn't favourable to Aotearoa, which resides on a geographical fringe. The nation's distance from other countries has often restricted knowledge and technological transfer and presented difficulty to contending as an exporter of international physical goods, with rising shipping costs and supply chain delays compounding this dilemma (Mindful Fashion. 2022). The interconnectivity of globalisation becomes a double-edged sword as drivers and issues in the international market also affect the nation's local market. Because of the former, when measuring the local market, global market trends to consider are -- environmental degradation, climate change, demographic changes, evolving business models, technological advancement, aging population, increasing ethnic diversity, urbanisation, increased remote working, the rise of gig economy, and automation technologies (Small Business Council, 2019a.).

The second obstacle is difficulties succeeding in the international market for Aotearoa fashion brands. This barrier is like a domino effect of globalisation, Where Aotearoa’s fashion designers have experienced a significant decrease in their overseas sales in the past decade (Catherall, 2021a). A globalised market also means that although there are trials and tribulations, Aotearoa brands want to succeed in the international fashion scene. (Catherall, 2021a) However, international development is becoming an increasingly expensive endeavour for these local labels (Glasson, 2018.) Whilst some Aotearoa brands reach this international acclaim, this growth is strenuous to sustain and often disconnects the business from its sense of origin and local customers (Glasson, 2018.).

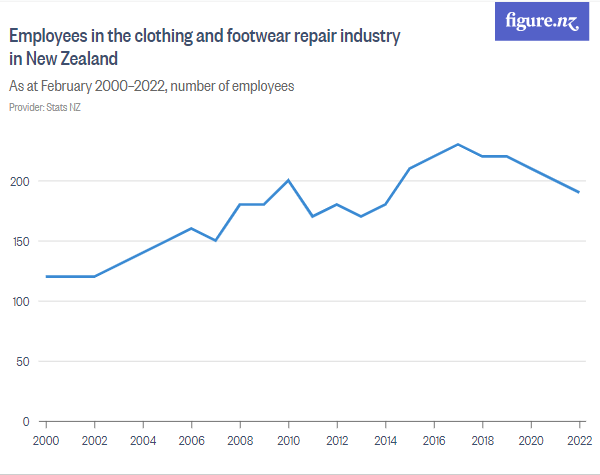

The third key obstacle was the lack of local resources and labour. Although there is enthusiastic support for local apparel manufacturing from New Zealand businesses, local manufacturing cannot meet this capacity demand (Mindful Fashion. 2022.). The main barrier to increasing local manufacturing seems to be the insufficient supply of technical clothing workers in Aotearoa (Mindful Fashion, 2022). The country is in a labour productivity slump, with an average income of 30 per cent lower than the OECD average (Small Business Council, 2019a). However, this deficit is exceptionally concerning for clothing manufacturing, which has continually declined in employment over the past 13 years (Figure NZ, 2022a.)

Figure 3: This graph depicting employees in the clothing manufacturing industry in New Zealand Illustrates the depressing decline of local clothing manufacturing, with a sharp decline between 2000 and 2002 and then a consistent downward slide over the next 20 years, with employment in 2022 resting at 1,950 workers. From Employee in the clothing manufacturing industry in New Zealand, by Figure NZ. 2022. CC BY 3.0

The shortage of workers is difficult to resolve as there is also little to no qualified technical fashion education course in NZ to build a technical fashion workforce (Mindful Fashion, 2022). With no educational spaces for technical sewing, most technical clothing workers have no education up to high school and are likely to have to be trained on-site (Figure NZ, 2013). There is also a lack of government intervention to support the increasing need for apparel manufacturing in NZ (Catherall, 2021a).

The History of Aotearoa’s Fashion Industry

My newfound understanding of the current state of fashion in NZ built a horizontal foundation for my contextual framework. Now, my research took a vertical perspective, observing the historical context of the local fashion industry. This knowledge illuminated vital insights into how the local fashion business has played out culturally and industrially throughout the decades. This information gave context to present and future trends of local fashion micro businesses and what historical factors may affect these trends. Apparel in Aotearoa originated with Maori communities passing down traditions of weaving, hand stitching and cloth dying, using materials in the neighbouring natural environments to forge handmade goods (Tolerton, 2010a). The arrival of Pakeha colonialists in the 19th century brought about pockets of commercial fashion businesses that were a mix of made-to-measure, home sewing, and basic ready-to-wear (Tolerton, 2010a). By the 20th century, fashion style became based in department stores, and ready-to-wear was the leading clothing, with dress-making catering to wealthier clients (Tolerton, 2010a). By the 1940s, a small textile and clothing manufacturing sector existed in NZ; however, it wasn't until WW2 that this industry saw significant growth and formation of an industry (Pollock, 2014b). With the disruption of supply chains leading to an absence of international fashion in the country, local entrepreneurial dressmakers and shop owners saw a business opportunity, providing locally-made clothing to the nation's population (Pollock, 2014b). After WW2, the government implemented high tariffs on international clothing to protect this boom in locally made apparel, which supported growth from the 1950s to the 1990s (Pollock, 2014d).

In the 1970s to 1980s, Aotearoa's fashion was built from many local ready-to-wear independent labels and boutiques that often started as stall holders in local markets and leasing storefronts in NZ cities' shopping strips (Pollock, 2014a). Other aspects of Aotearoa fashion saw changes, with designers adopting decorative embellishment and handmade printed textiles and fashion education shifting from apprenticeships to design courses (Pollock, 2014a). However, this golden age came to an abrupt halt from the 1990s onwards. Throughout the past half century, import tariffs on apparel have been in place to protect local manufacturing and businesses from overseas competition (Pollock, 2014a, Tolerton, 2010b). However, to contend with the shifting financial trends of globalization and rising consumer spending, 1992 apparel import tariff rates and restrictions had significantly softened (Pollock, 2014a, Tolerton, 2010b). This acceleration in imported garments led to a dramatic fall in the price of clothing, and locally produced garments could not contend with low-cost offshore production (Tolerton, 2010b).

"While they were 80,000 people employed in the clothing industry in 1950, now only 30,000 people remain in the present fashion sector."

(Casey & Johnston, 2021, Pollock, 2014c).

By the early 2000s, many local clothing factories had closed, and apparel tariffs dropped to 10% in 2009 and were nearly removed by the mid-2010s (Pollock, 2014c). The threatened extinction of local manufacturing caused dramatic alterations to the operations of local clothing businesses (Pollock, 2014e). Many local labels set about manufacturing overseas, and surviving local manufacturers repositioned to undertake small runs for small and micro business labels (Pollock, 2014e). The government's attention moved away from apparel manufacturing and instead supporting independent designers. (Pollock, 2014e)

In the 2000s, many Aotearoa labels had critical international success (Pollock, 2014e). Local fashion businesses prioritize niche markets and focus on designing high-end quality and textile innovation (Pollock, 2014e). Local fashion shows were becoming more popular, and there was an increase in tertiary fashion courses (Pollock, 2014e). However, the 2000s lost footing after the 2007 financial crash (Gardner, 2018). NZ labels were squeezed of financial support, and progress in the international market was interrupted (Gardner, 2018.). The 2010s brought about further movement into e-commerce over brick-and-mortar for local brands (Gardner, 2018). Implementing sustainable, fair practices became important after the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse and the Annual Tearfund ethical fashion report 2015 (Gardner, 2018).

Micro-Business Operations

After exploring fashion in NZ, I need to understand the other value in my research topic, Micro-businesses. My research on micro-business led to some startling discoveries that reformed my entire investigative approach and gave me a far more precise perception of the nature of doing business in Aotearoa and what logistical factors come into play when discussing micro-businesses impact. This overview summarises four interests in microbusiness: definition, microbusiness in NZ, and advantages and disadvantages of running a microbusiness.

Definition

In NZ law, a micro-business is described as employing 0-5 personnel (Small Business Council, 2019a). This includes self-employed and independent contractors (Small Business Council, 2019b). Micro-business owners are often the key operators, handling the most workload, performance, and responsibility (Small Business Council, 2019b).

Micro-businesses in NZ

Aotearoa is a nation of micro and small businesses, which make up over 90% of all businesses in NZ (Small Business Council, 2019a). Micro-business accounts for a quarter of NZ GDP and employs 10% of the national population (Small Business Council, 2019a). Compared to most OECD countries, NZ has a notably higher percentage of micro businesses and a far lower employee count of what is considered a micro business, with most countries deeming 6-20 employees as a micro business (Small Business Council, 2019a). The financial outlook of surveyed micro-business owners seems optimistic, with 2/3 desiring growth in the next five years (Small Business Council, 2019a)

Advantages for Micro-business models

Technology advancement and e-commerce outlets mean that micro businesses can keep their operations on a small scale whilst still having opportunities for development and reaching international markets (Small Business Council, 2019a).

Although the revenue of micro businesses is less significant than that of large-scale corporations, this does not necessarily mean that profitability is lower (Leonard, 2019). Microbusinesses lose far less revenue in operations than large businesses because they have more control over their operations (Leonard, 2019). Microbusinesses have more awareness to adapt promptly to the needs of their customer market, market trends and their own needs, particularly when relying on in-house production and service on a made-to-order basis (Leonard, 2019).

Microbusinesses are more in touch with their customers' environmental, social and well-being needs than large corporations, with smaller fashion labels adopting sustainable, fair practices more quickly than more prominent fashion brands (Cernansky, 2022).

Obstacles to Micro-business models

While micro-businesses comprise most enterprises in NZ, they are often overshadowed by large corporations in the commercial market. Corporations' scalability provides swifter control over mainstream customer markets and better access to skilled employees (Small Business Council, 2019a).

Micro Businesses also have difficulty obtaining financial support, with large-scale banks often perceiving small businesses as high risk, and bankers usually will require collateral for lending (Small Business Council, 2019a)

A consistent issue described by micro-business owners was the lack of appropriately skilled staff to fit the roles needed for business development (Small Business Council, 2019a).

Although microbusiness owners had an optimised outlook for growth, they also experienced a lack of coincidence from people in their sectors about the success of developing growth as a microbusiness (Small Business Council, 2019a).

Primary Investigation

Upon constructing a robust contextual framework, I shifted my focus to obtaining primary research on my subject matter. These in-person experiences provided crucial data to test hypotheses and compose analytic statements in my findings. After observing the online presence of a few dozen NZ micro-businesses, I narrowed my interest to 4 Aotearoa-based fashion micro-businesses for which I would inquire as case studies for this project. I chose these four fashion businesses as I felt all were partaking in innovative business approaches that showcase various stances to participating in fashion business practices in Aotearoa.

This investigation was informed by a series of online observations of case studies' websites, their social media and in-person interviews, with further secondary research added to give additional context.

Celestial Corner

Celestial Corner is an alternative fashion brand based in Karaphange Road, Auckland (Celestial Corner, 2023a). Their products are created by a collective of local artists and artisans who create clothing and accessories that embrace eccentricity, freedom of expression and being yourself ((T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023). Clothing's price range can range from $29 to $517, with the average price being $200 (Celestial Corner, 2023a). The customer market ranges from young teens to mid-30s adults interested in art, fashion and handmade items (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023). The brand was founded by creative director Anita Tana, who works alongside Operation manager Chrissy Abing and Head of content creation and Spaced Studio Jeremy Cole (Celestial Corner, 2023a).

Celestial Corner started 2019 as an E-commerce alternative fashion store based in Australia. In 2021, they embarked on a high-risk, high-gain venture and set-up shop at the renowned New Zealand music festival Splore (Celestial Corner, 2023b). Upon achieving a successful outcome at Splore, their on-site purchasing experiences inspired a pop-up store and then a permanent lease at St Kevin Arcade, with a storefront opening in late 2021 (Celestial Corner, 2023b). Over the past year, Celestial Corner has seen significant growth, from hosting monthly markets, leasing commercial studio space, and business developments (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

Key Takeaway From our Interview:

The financial dilemmas of developing a micro business whilst sustaining pre-existing operations (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

Their aspiration for future development (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

The logistics of working with independent artists (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

Their thoughts on building customer relationships online and in-person (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

The importance of creating spaces for self-expression and supporting local creators (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023).

Figure 6: Celestial Corner Storefront at St Kevin Arcade showcases their alternative fashion, Since opening their store layout has seen through several stages of development. storefront showcases their alternative fashion, Since opening their store layout has seen through several stages of development. From Celestial Corner Storefront at St Kevin Arcade. By St Kevin Arcade, 2022.

Starving Artist Fund

Starving Artist Fund is a Tamaki Makaurau-based fashion brand founded by Natasha Ovely that creates socially conscious gender-neutral apparel that prioritizes individuality, quality design and togetherness (Starving Artist Fund, 2023). Their apparel is size-inclusive and ethically made in Aotearoa, from small runs to made-to-order [Starving Artist Fund, 2023]. Their price ranges from 167$ to 613$, averaging at 350$ (Starving Artist Fund, 2023). Her clothing is sold through e-commerce and wholesale channels (Starving Artist Fund, 2023).

After graduating with a fine arts major in sculpture and being employed in numerous industries, Natasha self-taught herself in fashion design and debuted her first Starving Artist Fund collection in 2018 (Starving Artist Fund, 2023). Five years later, Natasha has seen renowned success from being featured in 20+ publications, celebrity endorsement and being in multiple fashion shows (Starving Artist Fund, 2023)

Key Takeaway From our Interview:

Her exploration of circular practices (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022).

Discussing the many facets of running a micro business financially and personally. (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022).

The many difficult creative and financial realities of being a designer. (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Her experiences participating in independent and digital fashion shows. (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022).

Figure 8: International-acclaimed Popstar artist Lorde wearing Starving Artists Fund for Viva newspaper magazine. From Natasha Ovely, Sauce, 2022,

Figure 9: Starving Artist fund At NZFW in 2019. From About, Starving Artist Fund, 2019,

Baobei

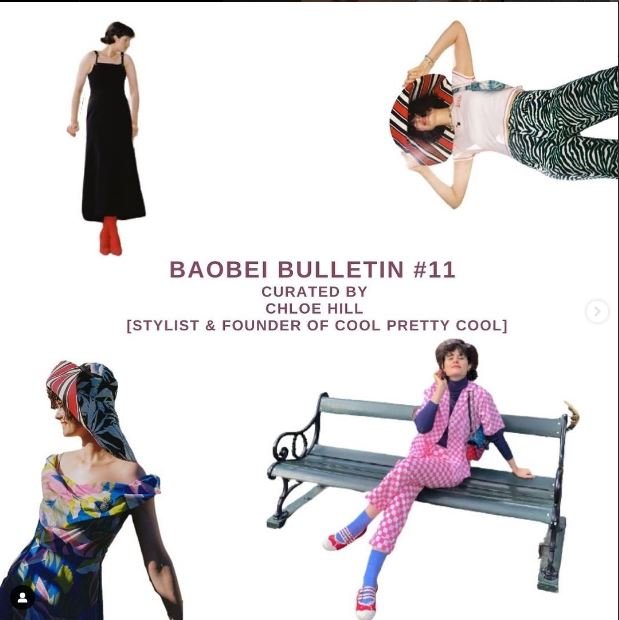

Baobei is an accessory and casualwear-based label that manifests authenticity, playfulness and self-love (Baobei, 2023a). Baobei is run by Grace Hsin-Yuan Ko, who is based in Tāmaki Makaurau and sells her fashion through e-commerce and wholesale channels locally and internationally (Baobei, 2023a). The brand has created a strong online presence centred on lifestyle branding with a genuine community-based approach (Baobei, 2023b). Their image and design tap into Gen Z trends of manifestation, affirmation and spiritual energy with a Y2K aesthetic (Robert, M 2023). Baobei prices range from $8 to $159, with the average price being $65 (Baobei, 2023a). Baobei's product list is accessory-focused, with versatile styling, affordable pricing, and occasionally experimental products (Ahwa, 2023). These products are produced in small runs or made-to-order (Baobei, 2023a). Her fashion designs reimagine her cultural experiences to emphasise self-love and welcome playful fun (Robert, M 2023).

Figures 11 and 12: On Instagram, Baobei Bulletin chats with local icons to give a down-to-earth atmosphere to their branding and market their lifestyle image through these influencers. From Baobei Bulletin #11 by Baobei, 2023, Instagram.

Reparation Studio

Reparation Studio provides alterations, repairs, bespoke and sampling services that offer a creative, sustainable, meaningful approach to fashion (Reparation Studio, 2023). Reparation Studio's technical practices invest in ' sentimental, the well-loved and the imperfect' clothing that values its origin (Reparation Studio, 2023). Repair services can range from $10 to $115, and alteration prices range from $30 to $75 (Reparation Studio, 2023). However, these prices are indicative only and may vary depending on the garment and the amount of damage or refitting (Reparation Studio, 2023)

Reparation Studio is run by Jessica Jay, who, after graduating with a BFA in fashion design and working in the local fashion industry, commenced her startup as a garment alteration and repair service (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022). Her work has many facets, including collaborating with collectives such as NVV World, publishing Patch Repair Workshop, and showcasing her artisan goods at independent fashion shows (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022, Reparation Studio, 2023.)

Key Takeaway From our Interview:

Discussing her recent works of purposely visible repaired garments, sourcing from Jimmy D faulty samples and damaged knitwear from Trademe. (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Explaining her garment revival process, which analyses damage and mending clothing through visually capturing embellishments that are sympathetic to damage. (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Her thoughts on sustainability in fashion and her sustainability ethos. (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Her experiences collaborating and sharing a studio space with other designers. (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Patch Repair Workshop, is Reparation studio's limited edition zine that is an introduction to modern hand-sewing and patch repair artisan techniques and practices such as patch collage, stitch sampler, and developing a personal stitching style. Her book offers costumers the ability to learn artisan practices as way to extend garment lifetime usage. From Patch Repair Workshop. by J. Jay, 2022, Blue Flower Texts,

Results

by securing our contextual framework that defined and framed the variables within the report, we solidified our approach to investigating and analysing this paper. Through this contextual and investigative knowledge, we can now form an analysis of findings using the living standard framework as a measurement tool to measure impact.

Natural Environment

Our findings will connect our contextual and primary research and weigh the impact of variables within this research report. Through the perspective of the living standard framework, we can assess ten findings impacting the fashion industry in Aotearoa.

Finding 1: Local fashion micro-businesses are key innovators for sustainable systematic change and are rethinking fashion business models.

Our contextual research of micro-business operations mentions that micro-businesses are drivers of sustainable practices and are more aware of social-political issues (Cernansky, 2022). This claim holds from observations of case studies' practices. All the brands we've studied are taking action to influence a more sustainable future, where clothes have deeper emotional durability and implement longevity in their design through circular practices and high-end quality craftsmanship.

In particular, Celestial Corner and Reparation Studio are exploring more niche business models that reframe the methodology of fashion operations. Celestial Corner relies on local artists and creators' products, providing them with a commission model business for online or in-person sales. Collective-affiliated artists also have access to utilised pop-up spaces and their commercial studios. Reparation Studio take routes in traditions of fit-to-wear similar to that of dressmaking of 19th-century NZ business except with a modern twist (Tolerton, 2010a).

Reparation Studio highlights the importance of these many sustainable practices to diversify the range of system-changing approaches in fashion;

"When you're looking at sustainability and the fashion industry, there is no one answer to it; there needs to be these multi-facet practices and ideas coming through."

Reparation Studio (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022)

Finding 2: Microbusinesses are drivers of circular slow fashion practices.

My contextual research noted that NZ fashion is interested in sustainability and localisation. This interest likely comes from several factors, but I hypothesise that New Zealand's appreciation of outdoor environments and Maori cultural practices has created a society that values the environment (Environmental Foundation, 2018).

My case studies provide sustainable apparel at local markets by centring their practices on circular and slow fashion techniques. Key design elements of circular and slow fashion from our case studies included employing secondhand materials, designing for longevity, small run to made-to-order production, upcycling services, and promoting local, sustainable creators.

Circular slow fashion practices are of decisive importance for the future of NZ to reduce environmental loss and CO2 emissions. NZ already has an appalling track record of being the largest producer of waste per capita and has the lowest recycling of any OECD country (Casey & Johnston, 2021)

From a financial perspective, these practices are also particularly profitable and have the potential to surge revenue for fashion microbusinesses, with circular slow fashion models having a forecast growth of 3.5% presently to 23% by 2030 ("Data point," 2022).

Figure 15: This model depicts how circular fashion functions as a closed loop model, where apparel can be designed and reuse through this practices. the goal is to increase longevity and garment life usage as a strategy for mitigating resource over-consumption. From What is Circular fashion , by C. Lissaman, 2019, Common Objective

Financial and Physical Capital

Finding 3: Fashion micro-businesses apply longevity in their work by producing emotionally and physically durable products.

From observing our brand's practices and products, there was a clear emphasis on creating products with quality and longevity. All our case studies practised emotionally durable design and quality control by providing community, handmade artisan craftsmanship and unique one-off pieces.

Notably, Starving Artists' work focuses on creating high-quality goods that are size-inclusive and versatile styling. Reparation Studio's business model centres on longevity, selling services that make meaningful restored items through alteration and repair services.

Figure 16: Reparation Studio's embellished restored apparel. Reparation Studio has strong emotional design consideration and quality control in her work, with some restoration requiring "65 hours of hand yarning" (Jay J, personal communication, November 11, 2022). From repairs, Reparation Studio, 2022

The importance of designing for longevity is that it allows customers to wear garments for longer and more often (Abbate et al., 2022). This quality control is essential for the NZ market, with over half of the survey respondents describing their garments as "out of season, unfashionable, or they're tired of wearing them." (Catherall, 2021b) If garments were worn for longer, it could also reduce environmental impact by 49% (Redress, 2022).

Finding 4: Local fashion micro-businesses target their growth into niche markets; however, this tactic can be a double-edged sword.

A niche market is a minority group of consumers with similar buying behaviour, lifestyles or demographics (Bailey et al., 2008). Local fashion micro-businesses are delving into these groups to sustain their financial growth by relying on market gaps in niche consumer spending (Small Business Council, 2019a). This approach indirectly competes with oversaturated mainstream markets heavily operated by large-scale businesses (Bailey et al., 2008).

Our case studies present several approaches to excelling in niche markets. Celestial Corner has created a marketplace entirely for alternative fashion, which sells local artisan goods to build its brand image rather than doing conventional offshore bulk production. Starving Artist's Fund explores clothing tailored to embracing marginalised voices.

Her business promotes small-scale QBIPOC creators, and her designs explore size-inclusivity, gender neutrality, and social-political consciousness. Baobei products provide physical manifestation and digital community to Gen-Z alternative lifestyles of affirmation, spirituality, and authentic self-love.

There are several reasons why niche markets can be so lucrative for micro-businesses; these include:

Less competition in a targeted market (Bailey et al., 2008).

A clearer perception of goals and customer market (Bailey et al., 2008).

Offers businesses the opportunity to specialise their skills and knowledge. (Bailey et al., 2008).

Can charge higher prices for a product in high demand for a niche market. (Bailey et al., 2008).

Customer loyalty. (Bailey et al., 2008)

However, Although on paper, niche markets appear as lucrative ventures for micro-businesses, this approach can also be incredibly challenging to thrive in the long term. Personal observations from my interviews, in particular with Starving Artist Fund, indicated that exploring creative aspirations in a niche market approach could be a high-risk venture with low to high returns and periods of economic instability;

"be prepared that if you are creatively motivated know there will be financial instability in your life."

- Starving Artist Fund, (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022).

My contextual investigation provided possible explanations for these struggles. Although Aotearoa's micro-businesses launch significant innovations, they struggle to maximise this growth due to lacking resources and labour to specialise, sustain their finances and develop economies of scale (Small Business Council, 2019a).

NZ is a country where micro-businesses constitute more than 90% of NZ enterprises, and Aotearoa's clothing industry is built on micro-businesses that rely on niche markets. (Small Business Council, 2019a, (Tolerton, 2010b) This abundance of micro-businesses could oversaturate local targeted markets, presenting unwelcomed high competition for NZ fashion micro-businesses when entering a niche sector (Chron Contributor. 2020). A competitive market with a small consumer demographic can lead to a shrinkage in loyalty and profitability of niche customers when there is a wide range of product outlets ("Niche markets, 2021").

My contextual investigation highlights a possible hypothesis of another underlying barrier: Aotearoa has far fewer local niche fashion consumers than foreign nations. Although national consumer spending on apparel will increase dramatically over the next few years (Degenhard, 2023), I predict these buying habits will be steered at mainstream fashion outlets. I reason that New Zealanders often struggle to express themselves through alternative fashion due to cultural barriers. This is caused by NZ society being a conformist culture, examples being cultural phenomena like tall poppy syndrome, where individuals are criticized for trying to stand out. (Kirkwood, J. 2020, Levine, S. 2012.)

Human Capability

Finding 5: Fashion micro-businesses consider the well-being of their customers.

In my primary observations and interviews, I noticed that the purpose and goals of case studies were deeply invested in supporting the well-being of their customers. Although they had similar values on well-being, each business took a different approach to satisfy this need.

Baobei positions customer well-being at the heart of their goods through emotionally durable design, which is complemented by brand lifestyle marketing that promotes authenticity and self-love. Celestial Corner considers well-being by providing a unique space to explore alternative eccentric self-expression without discrimination. Starving Artists Fund contributes to customers' well-being by designing gender-fluid, size-inclusive products that regard the needs of marginalised groups in mainstream fashion.

These approaches support well-being by accommodating the emotional needs of customers who are often marginalised in mainstream fashion and are looking for meaningful relationships with their clothing. (Kam & Yoo, 2022). Improving well-being is of pivotal value to Aotearoa as there has been a distressing escalation in poor mental health in past years. Surveys noted a deterioration in the NZ’s population mental health, previously at 22% in 2018, climbing to 28% by 2021 (Stats NZ, 2022).

Finding 6: Local fashion micro-businesses continue the legacy and traditions of New Zealand fashion.

While comparing my historical contextual investigation and case studies, I identified a notable overlap between past and present trends relating to crucial aspects of human capability. I concluded that these micro-businesses sustain a legacy of local innovation and traditional Aotearoa fashion design.

Our previous findings have highlighted the many approaches our case studies use to generate innovation. Based on observations, I propose that their innovative success is attributed to their persistence, patience, and taking action on their ideas.

"You're gonna have a lot of rejection, but who cares? Otherwise, your gonna be too shy, that doesn't make any sense." - Starving Artist Fund, (Ovely, N, personal communication, November 11, 2022).

"five-second rule– taking acting action on an idea within five seconds of it popping into your mind." - Baobei, (Robert, M 2023).

This innovative perserving attitude is particular notably when compared to the burnout mentality of NZ mainstream fashion we brand industry players such as Kate Sylvester, commenting,

"I feel like it's been the most challenging conditions that we've ever experienced, just to make the product." (Ahwa, 2022).

This is a recurring theme with local microbusinesses pursuing growth against international pressures has been depicted in former eras. Global economic disruptions, such as WW2, show similar trends of entrepreneurial startups generating growth and establishing an independent local fashion market (Pollock, 2014b). Fashion market innovation in NZ has also been prominently forefronted by women entrepreneurs (Pont, 2020), such as case studies in this paper.

Further generational crossovers were identified, indicated by the generational shared knowledge needed to maintain human capability (The Treasury, 2021). Today's Micro-businesses display similar business approaches to the mid-20th century Aotearoa fashion industry; at the time, the industry was propelled by independent labels and boutiques, who showcase their locally made goods at local markets, pop-ups and fashion shows (Pollock, 2014a). This description is a near-spitting image of our case studies’s approaches in contrast to the modern fashion retail landscape. Our present micro-business fashion designers have embraced local generational traditions of applying decorative embellishment and handmade and printed textiles (Pollock, 2014a). The images below depict this heritage of surface design in fashion.

Figure 19: The Kaitaka Paepaeroa photograph above showcases the hand-woven, hand-dyed clothing techniques that play a significant role in continuing Māori ancestral knowledge and practices. From Ruhia Pōrutu's kaitaka paepaeroa by A. Tamarapa & P. Wallace, 2013. Te Ara

Figure 20: This 1940s embellished gown was pioneered by Flora MacKenzie, who specialises in surface design such as hand embroidery, appliqueing and beading. From Black lace evening gown with taffeta lining, New Zealand Fashion Museum, n.d.

Figure 21: 'Praying Mantis Munching On Head' Long Sleeve T-shirt & Figure 22: Embellished Repaired Sleeve Hem

Today, our case studies continue this design lineage, such as Celestial Corner collective artist, Repair Angel worlds airbrush hand-printed T-shirt, and Reparation Studio repair embellishment techniques. From 'Praying Mantis Munching On Head' Long Sleeve T-shirt by Reparation Studio, 2023, Celestial Corner & From repairs, Reparation Studio, 2022,

Social Cohesion

Finding 7: Micro-businesses are enabling spaces and products that emphasise individual self-expression.

The case studies' observations indicated a focus on providing self-expression through unique pieces and authentic expression.

Celestial Corner's merchandise offers freedom of self-expression for customers to partake in alternative fashion. Starving Artists Fund's ethos mentions undertaking to form togetherness through individuality. Baobei's brand image is based on concepts of individual self-expression, such as authenticity and self-love. Finally, Reparation Studio constructs garments through one-off unique pieces and fixes.

"It talks about the deeper psychological human need to be seen as you are and to express yourself through these pieces. People's desire to be themselves." - Celestial Corner (T, Anita, personal communication, April, 5, 2023)

I propose that this desire for self-expression in their brands occurs due to the cultural lack of individuality and authenticity in Aotearoa. This phenomenon is likely a side effect of NZ's paradoxical cultural standards. Further research comments that although NZ has a tolerant and socially progressive outlook, there is also immense social pressure to conform to homogeneous cultural standards. (Kennedy, 2000, Levine, S. 2012).

This effect plays out as a cultural phenomenon like tall poppy syndrome, which deters people from self-expression because of the consequences of standing out (Kirkwood, 2007). Microbusinesses are likely far more aware of this social anxiety, with over half of NZ entrepreneurs having experienced tall poppy syndrome in their role (Kirkwood, 2007).

Finding 7: Micro-businesses are enabling spaces and products that emphasise individual self-expression.

Whilst physical product clothing is vital to the existence of fashion, it is also about fashion bringing people together through shared culture.

Case studies engaged in many strategies to develop community and togetherness. Celestial Corner's experience with in-person retail at Splore 2021 inspired their installation of a brick-and-mortar store. They invested their operations into launching alternative community spaces such as markets, raves, and exhibitions. At the same time, Baobei goes beyond using digital platforms as a merely commercial brand portfolio but as a space where Baobei can engage with customers and associates on a more personal level.

The need for the production of connectivity can not be understated, with The Ministry of Business, innovation and Employment stating that a " strong sense of community is important for the current and future well-being of New Zealand" (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment, 2021). This sense of community has become increasingly under pressure as statistics on loneliness in a post-COVID-19 society show a jump from 27% of citizens felt lonely in 2018 to 36% in 2021 (Stats NZ, 2022).

Figure 23: Celestial Corner lease of St. Kevin markets is a monthly highlight of the broader First Thursday markets on Karaphange Road, where local community can interact with local alternative fashion creators and artists' stalls. From The Celestial Corner Mid-Month Market, Celestial Corner, 2023

Discussion

This report highlighted the stark reality and promising future of micro-business in Aotearoa. My final prediction is that for the full potential of micro-business, centralisation of microbusiness ethos and action or government intervention to support micro-business in the fashion sector. The key to maximising this market potential is a large-scale national discussion that brings together fashion industry players, educators, and government leaders to discuss how to best pursue the opportunity that the fashion microbusinesses market growth can offer.

I now better understand the nature of the fashion industry and Aotearoa's economy, as well as many obstacles and opportunities of operating a fashion business in NZ that intertwines with our history, culture and law. Micro-businesses have a lot of potential and unique benefits to pursue systematic change in NZ's fashion industry; however, for my career journey, Aotearoa isn't the most efficient place to begin such an endeavour. However, if established industry players were to start this discussion in the next half-decade, new innovative developments in the fashion business could occur here.

Although this piece is extensive, I have made a strong linkage between all areas of this paper, and I believe all my findings are relevant to this discussion. My report has taken full advantage of this brief to explore my research and investigative practices and produce a work worthy of discussion for everyone involved.

The biggest lesson for my research practices was learning the limitations of data. Although my findings have real-world indications, they only indicate 2D estimations of a 3D world. This awareness of data limitations makes me feel uncertain yet unbound. To explore similar research subjects in the future I need to better understand financial knowledge, jargon and data.

Conclusion

My contextual investigation of 3 key areas and primary investigation of 4 case studies converge to 8 findings that assessed fashion microbusiness's impact on the four aspects of the standard living framework. I found that the case studies significantly affected all four elements of my finding framework. This research report has enhanced my knowledge of several fields, including microbusiness operations, fashion industry trends and Aotearoa's economy. This has also allowed me to improve my ability to measure, investigate and analyse data through organic approaches and utilising unfamiliar research frameworks. This paper has also solidified my desire to attempt a master's degree overseas to gain further opportunity and perspective in a new fashion and cultural environment.